I wrote in “Israel vs. International Law: Who Will Win?” (June 19, 2024):

Never before the complete incompatibility between International Law and Israel has been more blatant. This is cause for hope, actually, because in front of such evidence, world leaders are joining in the realization that one of the two must go. Israel and International Law cannot coexist on this planet. And the prospect of a nuclear world without International Law is terrifying.

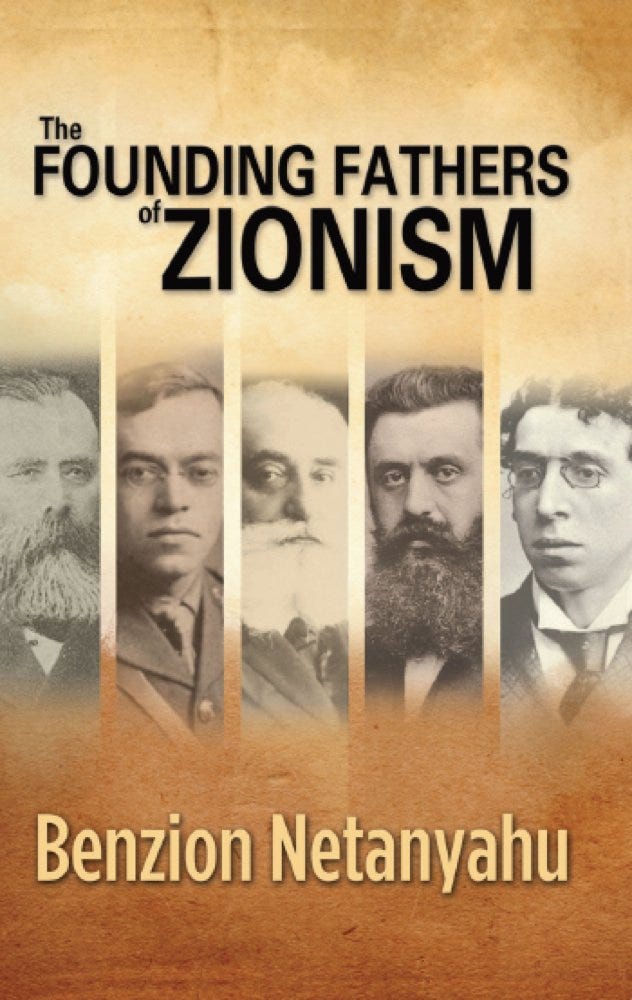

I argued that Israel’s contempt for International Law stems from Israel’s confidence in his Divine Right: being “chosen” means that man-made International Law doesn’t apply to you. However, I found a new perspective on Israel’s insane relation with history by reading Benzion Netanyahu’s book, The Founding Fathers of Zionism (2012).

Benzion Netanyahu (B.N.), born Mileikowsky, was Bibi’s father. He died in 2012, the same year that book was published in English. He was an honorable historian of Judaism and Zionism. I find his historical analysis of Zionism very helpful for understanding what his son is now trying to achieve, in the same way that understanding the political philosophy of Joseph P. Kennedy helped me to understand his son’s policies.

B.N.’s book is a compilation of five biographies (Leo Pinsker, Theodor Herzl, Max Nordau, Israel Zangwill, and Ze’ev Jabotinsky), but there is a clear structure to it. One leitmotiv, which is more implicit than clearly expressed, is that Herzl’s “Political Zionism” failed, not because it was badly conceived, but because it was badly applied by his successors, who lacked vision and determination. “We are suffering from this feeble spirit to this day, paying dearly for every deviation from Herzl’s path,” B.N. writes. Because things didn’t go according to Herzl’s plan, Israel has been lagging behind history, never able to catch up, and painfully aware of it. This may explain why Israel is increasingly turning to the biblical plan instead, and betting on God’s last-minute intervention.

After his offer to buy Palestine from the sultan was rejected (“If His Majesty the Sultan were to give us Palestine, we could in return undertake to regulate the whole finances of Turkey,” he wrote in The Jewish State), Herzl betted on a world war that would lead to the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire, which would be the perfect and unique opportunity for Jews to claim Palestine under the justification of national self-determination. What had to be done in the meantime was to make sure that the “right of sovereignty” of the Jews “be secured through political guarantees—that is, upheld legally by the great powers.”

It was clear to him that the moment of opportunity would come. He could not know for sure whether it would take five years or ten or twenty, but he knew it would come. He also understood that in order for that precious moment of opportunity not to pass in vain—the nation had to be prepared, and all its resources ready to seize and take control of it.

Herzl first concentrated his diplomatic efforts on Germany, but it was in England that things started to look promising, thanks in part to the recruiting of Israel Zangwill; “Zangwill was the first to speak in a direct manner about Zionism to the upper circles of British politics,” and to Lloyd George in particular, “a close acquaintance of Zangwill’s from the start of his Zionist activity to the end of his days.” During a trip to England in 1895, Herzl noted in his journal that: “The center of gravity has shifted to England.”

Herzl died in 1904, at the age of 44. Ten years later, “[t]he great moment came, as he prophesied, bound together with the storm of a world war.”

Herzl’s political activity resulted in the fact that the Jews, whom he had united in a political organization, were recognized as a political entity, and that their aspirations, which Herzl had publicized and proven their significance for the world, became part of the international political system. Indeed, due to the war, those aspirations had become so important that the major powers turned to the Zionists.

Thanks to Herzl, “the agreement of the League of Nations to Zionism was ready before that body was even established.”

And yet, the plan failed, and the window of opportunity soon closed.

While we generally see the Balfour Declaration as a major success for Political Zionism, B.N. sees it as a partial failure. Instead of seeing the glass half-full, he sees it half-empty. The Zionists failed to get a British commitment for “a Jewish State”, and all they got was the vague promise of a “Jewish home”. The world refused to upgrade that promise at the Paris Peace Conference (1919-20), and the British would soon start to interpret it in a minimalist way.

For that failure, B.N. blames “those who conducted the negotiations in the name of the Jewish people and afterwards conducted its affairs. When there was a need to display the courage to rule of which Herzl spoke, when there was a need to dare and to demand from the world a Jewish state and the power to rule over that state, this demand was not heard from the mouths of his successors.”

The failure could have been fixed, according to B.N., if after 1920 the Zionists had applied sufficient pressure on the British to give them control of the administration in Mandatory Palestine. But the man who was in position to apply that pressure, Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, was simply too … British.

B.N., as we know, was from 1940 onward the assistant to Ze’ev Jabotinsky (1880-1940), whom he greatly admires. In his chapter on Jabotinsky, he underlines the conflict between Jabotinsky and Weizmann. Jabotinsky believed in the necessity of using every possible means of pressure on the British to force them to accept vital Zionist demands, while Weizmann preferred to abstain from demands which had, in his opinion, little chance of being accepted. “The starting point of our diplomatic work in the future,” he wrote in the eve of the 1927 Zionist Congress, “must be—as it was in the past—maintaining our friendly relations with the Mandatory authority and with its emissaries in Palestine.” This proved a failure anyway, since Zionists had to resort to terrorism against the British in the 1930.

Unlike all the books written in English by his son Benjamin, which are propaganda for gullible Americans, B.N.’s book is aimed at a Zion-friendly Jewish readership, and can be taken as an honest perspective shared by many Zionists. It therefore goes a long way toward explaining the policies of the current government. These policies are driven by a sense of having missed the train of rational history, and by a desperate, irrational effort to catch it up through some biblical time warp, through a Bronze-Age type genocide.

That Israel is out of step with Hegel’s “World Spirit” (Weltgeist)—the invisible force advancing world history—is a hopeful way to look at current events. In fact, from that perspective, it appears that Herzl came too late himself. Benjamin Disraeli had been better positioned in the timeline, and he did try to put the “restoration of Israel” on the agenda of the Congress of Berlin (1878). But then, it was too early: Jews were not interested by Palestine. Which proves the point that Zionism is ever anachronistic.

Although B.N.’s historical survey stops after WW1, it is interesting to consider what happened next from the same perspective. Long story short: in 1920, Churchill volunteered as the Zionists’ wildcard, with his bold article “Zionism vs. Bolshevism: a Struggle for the Soul of the Jewish People”. The following year, he was appointed Secretary for the Colonies, and signed a White Paper that set no limitation to Jewish immigration in Palestine, while turning a blind eye to the creation of the paramilitary Haganah. The first Arab revolt led to his removal from government, and the emission of a new White Paper limiting Jewish immigration to 75,000 over the next five years. Hitler’s invasion of Poland forced an appeasing Chamberlain to resign, and opened the way for the World War that Churchill and the Zionists so intensely desired.

But then again, the Zionists got their glass only half-full, in the form of a ridiculously impractical U.N. Partition Plan. What to do? Take it anyway and assassinate the U.N. representative Folk Bernadotte.

The point I’m trying to make, here, by following B.N.’s logic, is that the history of Zionism can be seen as a history of failures, rather than a history of successes. Israel has missed every train, while continuing to claim they should drive the locomotive. Israeli leaders are at a loss on how to deal with this cognitive dissonance, and as usual, their only hope is another world war. But world leaders have grown wiser, at least in the East, and they don’t seem to be getting it.

Israel has failed in three major ways:

First, as B.N. shows, Zionism has failed to manipulate national governments and international institutions to the point of getting their colonization and ethnic cleansing of Palestine rubber-stamped by International Law. Therefore, Israel has remained an outlaw, a rogue state, and now a criminal state in the eyes of the international community. If they could, they would assassinate UN Secretary-General António Guterres, but that would be as futile as their assassinations of Hassan Nasrallah and Yahya Sinwar. Israel has lost all legitimate membership in the international community, and it is a matter of time before they are punished for their crimes … and their lies.

Second, Israel has failed to break Arab resistance. Herzl understood it as a sine qua non condition, and so did Jabotinsky, who wrote:

As long as even a spark of hope nests in the Arabs’ hearts that they may succeed in getting rid of us, there are no pleasant words and no attractive promises in the world for which the Arabs will be ready to give up this hope of theirs—and this is precisely because the Arbas are not a rabble, but a living nation. And a living nation is ready for concessions on fateful issues such as these only when no hope is left for it to change the situation and when every breach in the iron wall has been sealed.

While Israelis have lost all decency as a nation, the Palestinians have earned, through their heroic resistance and extraordinary resilience, the right to own their ancestral land and govern themselves. No matter how we consider Palestinian nationality before the Nakba, no other people have now more legitimacy as a nation. If “divine right” means anything, it applies to the Palestinians, not to the Israelis.

Third, Israel has lost the information war. Their control of the narrative and of worldwide public opinion has collapsed, thanks to the miracle of Internet. Here again, they are one step behind. Their 9/11 coup came too late: if was filmed and exposed on Youtube within five years. They could have gotten away with it, perhaps, just five years earlier. Now their war crimes are filmed and exposed to the world instantly. The dead Palestinian children speak to the world. Conversely, the 40 Israeli beheaded babies have failed to convince.

Of course, Israel has scored some successes. By assassinating Kennedy and putting Johnson in the White House, they acquired the Holy Nuke, by which they can now secretely blackmail every state with their Samson Option. But again, they have missed another train here. For despite trying for twenty years, Netanyahu has failed to drag the U.S. into bombing Iran, and it seems that Iran has the Nuke now, plus the protection of Russia. Too late.

One big success for Israel is their total control of U.S. foreign policy. Kennedy famously said when taking office: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Now the motto for both candidates to the presidency seems to be: Ask not what you can do for your country, ask what your country can do for Israel. But again, time is running short, for the U.S. is at the end of its rope. What will Israel do without America’s protection? “America made me do it” (the Chomskian excuse) will not convince.

When Kevin Barrett referred to this article, I asked for a link. I'd been subbing all the 'irregular' Unz bloggers to make sure I didn't miss a new post, but couldn't find it. And now I find I've been missing the motherlode! Glad to be tapped in.

Very thought provoking and unique perspective in this article, Laurent. On the history, I feel like you fill in the missing pieces on a puzzle I've been staring at without seeing the shape of the design. I knew what Churchill did for the Jews in WWII, but not that he was Secretary for the Colonies prior.

The Messianic desperation seems very real. I wonder if we'll see another faked assassination of Trump by a Palestinian-American, only to whisk him off to Epstein Island and put Vance in charge. Trump would be the martyr getting red-blooded American men to fight in the Middle East, while Vance takes care of business.

On your interview with Mees Baaijan I wrote: "I'm glad that Laurent has done the research on Hitler as an agent of the Rothschilds/ City of London. People I respect on my stack have presented solid evidence on both sides. At the moment, I'm leaning that he wasn't. The economic plan I attribute to Feder but his own words are too brilliant to be an actor. Julius Skoolafish has been posting long quotes from Mein Kampf and his speeches, along with The Green Book by Qaddafi and from Mussolini. Everything we've been taught is upside down.

"Where I differ from Mees is that 500 yrs is too short a timeframe. The system of coinage and taxation, as I talk about in my book, was launched to make us complicit in the conquest and enslavement of our neighbors. It was in the same timeframe as the Axial Age religions, although that might have been as late as 700 CE from Laurent's Anno Domini.

"The Torah talks about these techniques with Joseph turning all the Egyptian farmers into indentured servants--to this day, as he brags. The system of slipping Hyksos women into the harems of royals is in the Torah (repeatedly) and the history of the Hyksos of Avaris infiltrating and usurping the role of Pharaoh. Tubal-Cain was the name of metalworkers or goldsmiths. Cain is given protection by Yahweh in his travels. Was this coinage?

"There's always a tribe of landless, nomadic men who lay siege to the towns until they turn on their own leaders and kill them to have 'peace.' According to anthropologists, shepherds were feared and also drove away the wild game of hunters. They rode horses and carried a curved blade like a scythe, the symbol of the grim reaper. Did the Hyksos become the Royal Scythes, from whom Constantine is said to hail?

"Along with the question of who are the men behind the Wizard of Oz projection of Yahweh is who are the puppetmasters now. I agree with both Mees and Laurent. The 'Jews' or Ashkenazis are just the latest iteration of 'Yews' in the Hebrew pronunciation, or Ewes being used. The 1% narrows it down but it's more likely the .001% or 1 in 100,000 or even a million."

It's a real pleasure to read you and listen to you, Laurent.

Been loving your brave work.

I knew it was bad for many yrs but it took me til I stumbled on Leon Rossleson's MEDIUM page and read a few of his essays to be really wow. He was one of those types, a-la Weininger, and the whole deal (political Zionism) is based on that fundamental self-awareness, to paraphrase Herzl, 'it is with them wherever they may go' they sure seem to have brought it to the Cursed Land (I am committed to call it that, what it is, for the rest of my life). I'm still in NYC (need to move ASAP) and ny closest circle is two Jewish Boomers native New Yorkers, born in 1949. Totally different personalities but on the same page about a whole lot of things, both very Liberal, progressive (whatever that means, I take it to mean 'you are free to choose between any of the choices WE say are legit' anything else is Fascist etc)

but neither seems to have read Herzl’s writing, and both are highly educated, one at Harvard the other one at CCNY. Latter one has been yelling at me that 'people like me' (= the disgusted by politricks who's never, ever voted) shouldn't ever be allowed to vote ! Doesn't notice the inconsistency in his thinking.

Endless accusations of being Right wing, which is interesting and one of the cruxes of the matter. So I recently brought up this question to the other friend, the Harvard educated liberal, Jewish NY boomer: 'D. Pls I seriously have to ask , why you think it is that anything Left-wing is OK, even hip, still today, but the other wing is , has been and will likely remain the not good wing. Since we have ample evidence throughout the 20th century that Left-wing systems led to comparable if not higher numbers of people being slaughtered, how does the Left still get a pass?" His answer took a few secs although I bet he must know it's a dumb answer he gave me. "Because the Right's rhetoric is all hate" LMAO when I bring up reading an old Jewish anti-war folk songwriter like Rossleson and his MEDIUM pieces wit the CCNY guu it's always this:

'Get out of my house! Keep Jews out of your mouth!'

Been saying forever, the Middle East and the US foreign policy towards it has been the albatross around the West's neck since the early 60s. After going thru Final Judgment, it's clear to me.

I need to buy your books Laurent. Rossleson's in his 90s I thought he stopped publishing but now seeing a 2024 piece, you're prob familiar but I learned a thing or two with his blog too: https://rosselson.medium.com/