The problem with Atwill’s theory

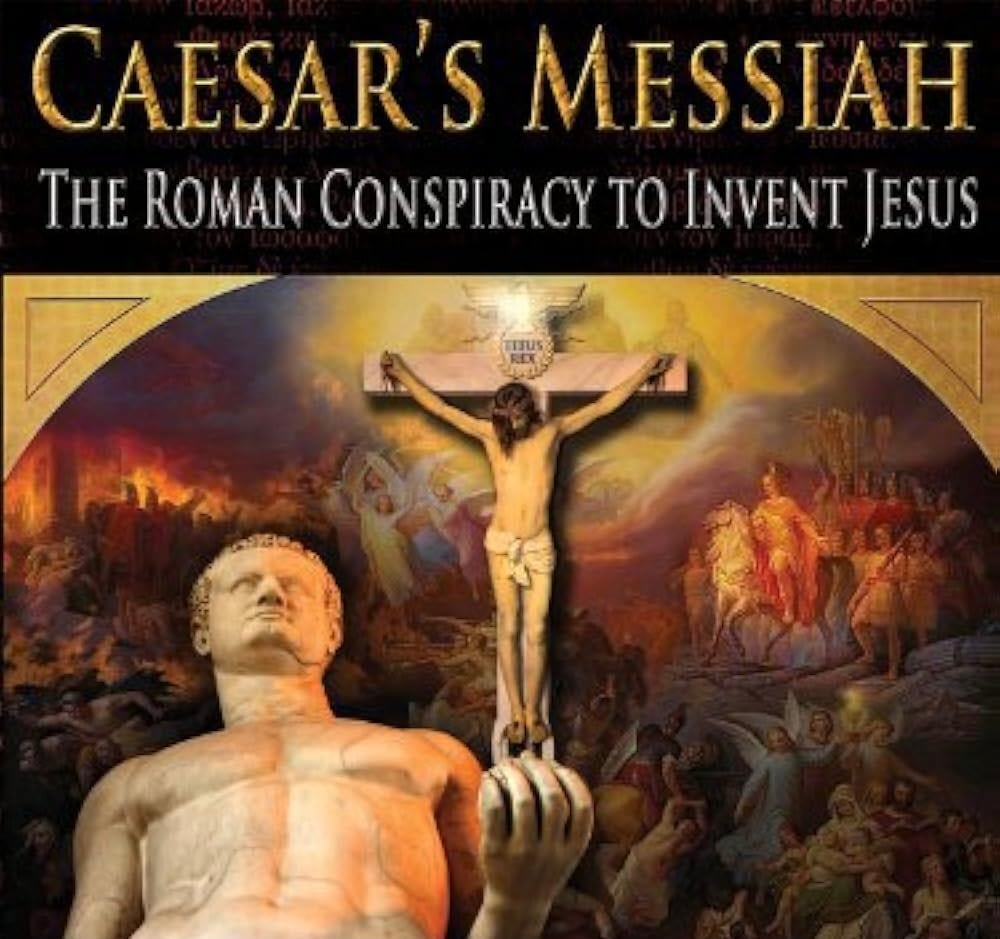

Here is my critical assessment of Joseph Atwill’s theory, presented in his book Caesar’s Messiah: The Roman Conspiracy to Invent Jesus (first edition, 2005), illustrated in a 2012 documentary that totals millions of views, and recently summarized by the author for the Unz Review.

Atwill’s theory is that Jesus and Christianity were invented by the imperial Flavian dynasty (Vespasian, Titus, Domitian), with the help of Jewish friends who crafted the Gospels. Their main purpose was “to promote a more pro-Roman version of the messianic Judaism that constantly rebelled against Rome.” On the face of it, the theory is plausible and fits the historical context. The birth of Christianity is intimately connected to the events leading to and following immediately the Jewish War of 66-74 AD, and these events are the background for the emergence of the Flavian dynasty, which “lasted from 69 to 96 C.E., the period when most scholars believe the Gospels were written” (Atwill, Caesar’s Messiah, p. 10). Vespasian was the first emperor who was not from the Julio-Claudian dynasty, and the first military general to ascend to the throne, through what amounted to a military coup. The Flavians were therefore in need of legitimacy, and for that reason had an interest in religious propaganda. Moreover, the Roman Empire had a major “Jewish problem” that culminated under the Flavians. It was more than a “Judaean problem”: Seneca, tutor and confidant of Nero, is quoted by saint Augustine as charging that: “the customs of that most accursed nation have gained such strength that they have been now received in all lands, the conquered have given laws to the conqueror” (City of God, VI, 11).

The theory that the Flavian emperors and their Jewish or half-Jewish clients were involved in the fabrication of the Gospels is not completely new. The German historian and biblical critic Bruno Bauer defended a version of it in his second last book, Christus und Caesaren (1877), arguing for a strong influence of Seneca’s circle on the whole project.[1]

In 1979 was published a 30-page booklet by Abelard Reuchlin, The True Authorship of The New Testament, unmentioned by Atwill. Reuchlin also underscores the influence of Seneca’s circle, and identifies the authors of the New Testament (Gospels and Epistles) as being Lucius Calpurnius Piso and his son, in collusion with the Herod family to whom they were related. The aim was to create a peaceful form of Judaism to convert the Jewish zealots resisting Roman occupation in Judea. But the plan failed because of Nero’s pro-Jewish mistress (later his wife) Poppea, which led to the Pisonian conspiracy to assassinate Nero, which also failed. The evidence provided by Reuchlin is extremely disappointing, but his theory was taken up in 2018 by Henry Davis, who borrows some arguments from Atwill in Creating Christianity: A Weapon of Ancient Rome.

Atwill’s theory is also endorsed by James Valliant and Warren Fahy in Creating Christ: How Roman Emperors Invented Christianity (2018), where they bring in some unconvincing archeological evidence concerning the iconography of the earliest Christians.

Two centuries from Vespasian to Constantine

The “Flavian hypothesis” raises two major objections. The first problem is with the chronology. Atwill’s theory would make perfect sense if the historical record could document that the Flavians, rather than the Constantinians, were the first promoters of Christianity, or if the two dynasties were not separated by two centuries—roughly eight generations—of imperial hostility to Christianity.

The bottom line is that there is no record of any Roman emperor supporting Christianity before Constantine the Great (the subject of my previous post). Before Constantine, Roman administration consistently judged Christianity a problem, not a solution—although Christian tales of martyrdom are now deemed widely exaggerated.[3] The Antonine emperors (from 96 to 192 C.E.) intensely disliked Christianity, and Diocletian (284-305) tried to eradicate it.[4] There exist hints of sympathies toward Judaism from members of the imperial court (women, often), but no clear trace of sympathy toward Christianity.

The hostility was reciprocal. Despite the fact that Jesus expressed neutrality toward Rome in the midst of the explosive tensions in the Judaea of his lifetime, Christians’ attitude to the Roman Empire before Constantine cannot be characterized as friendly. In the Book of Revelation (chapters 17 and 18), Rome is cryptically called “Babylon the Great, the mother of all the prostitutes,” and doomed to end up in disease, famine, and fire.

Not all Church fathers, it is true, held such a dim view of the empire. In the first half of the third century, Origen saw the Empire as good for Christianity, since the Pax Romana made it easier for the apostles to “go and teach all nations” (Contra Celsus II.30). But not before Eusebius of Caesarea do we find the idea that Christianity was good for the Empire. In the words of Richard Fletcher, “Eusebius brought the Roman empire within the divine providential scheme for the world. It was an astonishing feat of intellectual acrobatics,” given that pre-Eusebian Christianity was mostly a world-denying, end-of-world-heralding religion.[5] Eusebius, of course, was Constantine’s religious adviser—or so he claimed.

Anyone claiming that some emperors before Constantine created, promoted, or just appreciated Christianity, has to assert that they did so in secret. This is not impossible, since, in Peter Heather’s opinion, Constantine himself had been a closet Christian long before he became emperor, having been secretly raised in the faith by his father and mother.[6] Although the Constantinians are not related to the Flavians, a spiritual filiation is not out of question, since members of the Constantinian dynasty, starting with Constantine’s father, consistently bear the nomen Flavius; but that is a very small nail on which to hang the extraordinary claim of some Christian initiation secretly passed on for two centuries among crypto-Christians Romans within imperial families.

The Flavian hypothesis requires an explanation for the 200-year anti-Christian gap between the Flavians and the Constantinians, and Atwill does not provide any.[7]

A religion for the Jews, of for the Romans?

The second problem with Atwill’s Flavian hypothesis is the contradiction between the claim that Christianity was designed to convert the Jews, and the reality that it ultimately converted the Romans. The Gospels’ storyline, Atwill writes in his recent article, was created mainly to “pacify Jews with a peaceful Messiah”. He insists on that motive in his book: Christianity was meant “to replace the xenophobic Jewish Messianism that waged war against the Roman Empire with a version of Judaism that would be obedient to Rome” (p. 21). The Flavians “created the religion to serve as a theological barrier to prevent messianic Judaism from again erupting against the empire” (p. 387) The imperial family “created the Gospels to initiate a version of Judaism more acceptable to the Empire, a religion that instead of waging war against its enemies would ‘turn the other cheek’” (p. 42). Christianity “was designed to replace the nationalistic and militaristic messianic movement in Judea with a religion that was pacifistic and would accept Roman rule” (p. 19).

If that is the case, then the Flavians enterprise not only ended up in complete failure (few Jews were converted, and Jewish messianism erupted again in the second century), but it actually backfired, since the few Jewish converts ended up converting the Gentiles. Atwill would also need to explain why Christianity, instead of weakening Judaism, banned all Gentiles’ religions except Judaism.[8]

Atwill does not address that obvious contradiction, but adds to the confusion when he mentions the possibility “that Christianity was designed to promote anti-Semitism—a concept that is plausible, historically. A cult that produced anti-Semitism would have both helped Rome prevent the messianic Jews from spreading their rebellion, and punished them by poisoning their future” (p. 63).

The two problems I have just mentioned are interconnected. What needs to be explained is both the 200 years it took for the Roman-made Christianity to become publicly promoted, and the mystery of how, in that period, it switched from targeting the Jews to targeting the Romans.

Those problems do not make the theory impossible. It is conceivable, for example, that Plan A failed, but was picked up and changed into Plan B much later. Henry Davis hints at that possibility in, Creating Christianity: “Christianity was ‘dead’ about the year 120 CE until Constantine revived it just after 310 C.E.” But more explaining is needed, and I haven’t found it.

What Christian Flavians?

Atwill relies heavily on dubious and inflatted circumstantial evidence. For example, he claims that his theory would explain “why so many members of a Roman imperial family, the Flavians, were recorded as being among the first Christians. The Flavians would have been among the first Christians because, having invented the religion, they were, in fact, the first Christians” (p. 33).

The “so many” Christian members of the Flavian imperial family are hypothetical at best. They are Flavia Domitilla, grand-daughter of Vespasian, as well as her cousin and husband Titus Flavius Clemens. But the tradition that they were Christians appears in the fourth century under the pen of Eusebius of Caesarea. In earlier non-Christian sources, they are said to have been charged with atheism, like many others who “drifted into Jewish ways” (Cassius Dio, Roman History, 67, 14). If we understand “Jewish” to mean “Christian”, there remains the problem that Clemens and Domitilla’s religious inclination was not in the taste of the emperor: Clement was executed, and Domitilla was exiled together with members of her entourage. In other words, if they were Christians, as Atwill assumes, then their story contradicts Atwill’s theory, and it takes a lot of nerves for him to pretend that it supports his theory.

Why another Pro-Roman Judaism?

The theory that the Flavians needed to create a pro-Roman version of Judaism supposes that such a thing didn’t exist. It did. We call it Hellenistic Judaism, and for the period we are discussing, we might just as well call it pro-Roman Judaism.

As far back as biblical history, and up to the present, we see the Jewish people divided between assimilationists and anti-assimilationists. At the end of the Hellenistic period, this tension led to the civil war documented in the Books of the Maccabees. Hellenistic or pro-Roman Judaism was dominant in the Diaspora, which accounted for two thirds of the approximately seven million Jews living within the Roman Empire (about 10 percent of the population). In broad strokes, the major inner tension within the Jewish community was between internationalist Jews and nationalist Jews, the former being well-disposed toward the Empire, while the latter were vehemently hostile to Roman rule. Internationalist Jews practiced proselytism, while nationalist Jews believed in ethnic purity.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Radbod's Lament to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.