Our Ruling Class: Lessons from Mosca, Machiavelli, and Attila the Hun

This article is simultaneously published here on the Unz Review.

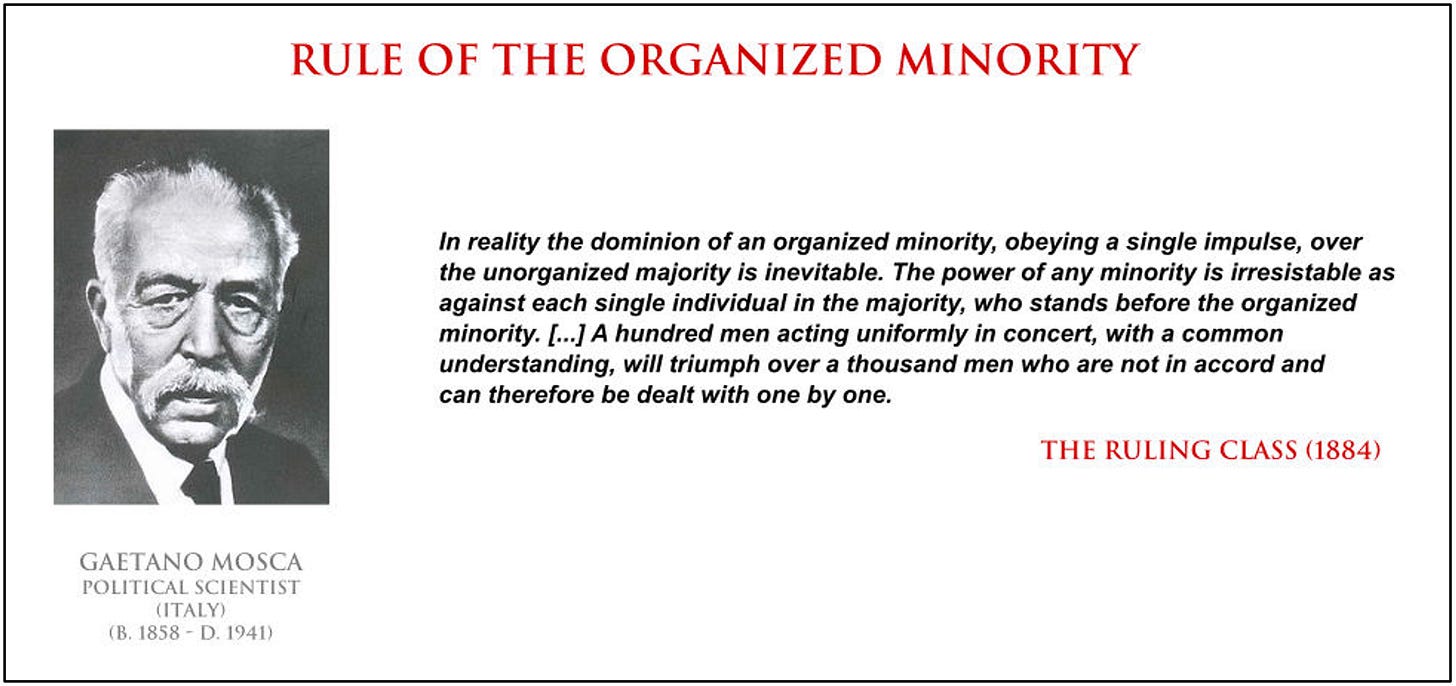

To understand how Israel has gained a near-total control over the American ruling class today, we must understand Israel of course, but we must also study the principles by which any ruling class operates. The perfect book for that is The Ruling Class, by Italian political scientist Gaetano Mosca (1858–1941). Mosca begins by establishing the following law (p. 50):

In all societies, from societies that are very meagerly developed and have barely attained the dawnings of civilization, down to the most advanced and powerful societies, two classes of people appear: a class that rules and a class that is ruled. The first class, always the less numerous, performs all political functions, monopolizes power and enjoys the advantages that power brings, whereas the second, the more numerous class, is directed and controlled by the first…

No matter what their internal divergences are, the ruling class is bonded by a high degree of solidarity: “the minority is organized for the very reason that it is a minority” (p. 54).

It follows that the main object of political science must be the study of various types of ruling classes. Mosca, p. 336: “We must patiently seek out the constant traits that various ruling classes possess and the variable traits with which the remote causes of their integration and dissolution, which contemporaries almost always fail to notice, are bound up.” Historians and journalists remain at the surface of historical events when they ascribe them to the decisions of heads of states, who are only, as a rule, the public faces of a ruling class, and sometimes not the main decision-makers.

A ruling class can be overthrown, either by a foreign conquest, by a coup d’état, by a revolution, or in more subtle ways that are not always immediately perceptible by the ruled. But any change of regime, even if provoked by popular uprising, leads to the formation of a new ruling class.

All this may seem quite obvious, but reading Mosca and pursuing this line of thought has modified my perspective on political regimes, on the illusion of Democracy, and on what Israel is up to.

Machiavelli

I discovered Mosca through James Burnham’s book The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom (New York, 1943). Like Mosca, Burnham stresses that: “Historical and political science is above all the study of the élite, its composition, its structure, and the mode of its relation to the non-élite” (pp. 224-5). Burnham classifies Mosca as a “Machiavellian”, among three other political thinkers who share Machiavelli’s realism—as opposed to the idealism that Burnham illustrates with another Florentine, Dante Alighieri. Mosca is definitely a disciple of Machiavelli, in the sense that the fundamental law that is the premise of his work had already been formulated by Niccolò Machiavelli in the early sixteenth century: “in any city, in whatsoever manner organized, never do more than forty or fifty persons attain positions of command” (Discourses on Livy, XVI, quoted by Mosca, p. 329). If we take that number literally, the actual number of persons in charge would represent 0.1 percent of the population in a big city like Florence, with a population around 40-50,000 inhabitants in Machiavelli’s time. But not every member of the ruling class is on active duty at all times, so that the proverbial One Percent seems a good rough estimate of the average ruling class, although a case by case study might show important differences, and a distinction could be made between the ruling class and the ruling élite within them.

Burham’s book changed my perception of Machiavelli, whom I knew mainly through Leo Strauss’s crypto-Zionist, ultra-Machiavellian interpretation. Burham p. 38:

Almost all commentators on Machiavelli say that his principal innovation, and the essence of his method, was to “divorce politics from ethics.” … this opinion is confused. Machiavelli divorced politics from ethics only in the same sense that every science must divorce itself from ethics. Scientific descriptions and theories must be based upon the facts, the evidence, not upon the supposed demands of some ethical system. If this is what is meant by the statement that Machiavelli divorced politics from ethics, if the statement sums up his refusal to pervert and distort political science by doctoring its results in order to bring them into line with “moral principles”—his own or any others—then the charge is certainly true. / This very refusal, however, this allegiance to objective truth, is itself a moral ideal.

Machiavelli was a firm believer in the Republic, which is defined as government by law (the same law for ruled and rulers alike), the only source of freedom in his view. That freedom, he emphasized, “can be secured in the last analysis only by the armed strength of the citizenry itself, never by mercenaries or allies or money” (Burnham p. 69). As he wrote in The Art of War (his only major work printed in his lifetime), a “people in arms” will restrain the “appetite” of domination of the grandi: “the unarmed rich man is the prize of the poor soldier.”

But Machiavelli also realized that a Republic is not possible under all circumstances. His immediate practical goal was the national unification of Italy, divided into city states constantly at war. “This fragmentation of Italy had left it open to an uninterrupted series of invasions, by adventurers, junior members of royal families, knights returning from the Crusades, kings, and emperors. Control over cities and territories shifted every decade, from Normans to Spaniards to Frenchmen to local bosses to Germans to Popes and back again” (Burnham p. 33). The unification of Italy, Machiavelli thought, could only be achieved by the bold action of a prince who could “take the lead in the movement of national redemption.” He wrote The Prince with that in mind, and dedicated it to Lorenzo de Medici, whom he saw, for a variety of good reasons, as the one man up to the task. The last chapter of The Prince is entitled: “An Exhortation to Deliver Italy from the Barbarians” and the Discourses on Livy contain lengthy discussions aimed at showing Italians how to defeat the forces of France, the Empire, and Spain and thus gain control of their destiny as an Italian nation. We tend to forget that the unification and independence of Italy were so much resisted by Europe’s princely and clerical class, that it was not achieved before 1860.

Types of ruling élite

According to Machiavelli, the uneven distribution between rulers and ruled is not only determined by the external constraints of social life; it is consistent with human nature, because the basic quality required for being part of the ruling élite is present only in a minority. Machiavelli calls that quality virtù, a word derived from the Latin vir, closer therefore to “virility” than to “virtue”. According to Burnham (p. 58):

It includes in its meaning part of what we refer to as “ambition,” “drive,” “spirit” in the sense of Plato’s thumos, the “will to power.” Those who are capable of rule are above all those who want to rule. They drive themselves as well as others; they have that quality which makes them keep going, endure amid difficulties, persist against dangers.

Virtù does not guarantee access to the ruling class, however, for each life is also dependent on the equally uneven distribution of fortuna, starting with the social inequalities inherited at birth. But virtù, precisely, is the ability to deal with fortuna: “the ruler-type of political man is one who knows how to accommodate of the times. Fortune cannot be overcome, but advantage may be taken of her” (Burnham p. 71). In Machiavelli’s view, Burnham writes, “men and states will make the most of fortune when they display virtù, when they are firm, bold, quick in decision, not irresolute, cowardly, and timid.” Mosca takes a similar view, p. 54:

ruling minorities are usually so constituted that the individuals who make them up are distinguished from the mass of the governed by qualities that give them a certain material, intellectual or even moral superiority; or else they are the heirs of individuals who possessed such qualities.

The last qualification is, of course, crucial. Powerful men try to make their power hereditary, which means that any ruling class practices endogamy and nepotism. The desire to pass on to one’s offspring the benefits of one’s achievements is natural, not evil. However, when the social mechanisms of hereditary power become too efficient, they inhibit the healthy renewal of the ruling class. For although the ruling class wishes virtù to be genetic, and will try to convince the masses that it is, it is not. A study of princely dynasties will often show that the grand-children of the founders lack the qualities to rule. That’s understandable: ambitious men who want to rise socially will develop more energy, more will to rule, than men who are born in the upper class. The degree of acceptance of newcomers by a ruling class is an important characteristic or any society. Impermeability will inevitably, in time, make any ruling class illegitimate in the eyes of the ruled, whatever the sophistication of its propaganda or mythology (royal blood, divine mandate, etc.). When a ruling class becomes too endogamous and sealed from the rest of the population, they lose their sense of shared ancestry and shared destiny with the ruled. They think of themselves as a superior race and become abusive, having to protect themselves from popular resentment by coercive means.

The worst case for the ruled masses is when the ruling élite is that of a conquering foreign nation that has eliminated or subjected the local élite. This has happened many times in the Dark and Middle Ages. But here again, the situation will vary depending on the character of the invaders, their policy towards the conquered, and their state-building project. Not all foreign conquerors are a parasitic ruling class: some engaged in state-building rather than just exploitation of natural and human resources.

The Republic

The solution to the age-old political challenge of a win-win relationship between the rulers and the ruled is the Republic, defined as the rule of law. It was the genius of the Romans to apply that Greek idea on a grand scale. Contrary to a common misunderstanding, even the Roman Empire remained, in theory and to a large degree in practice, a Republic: it was never forgotten that the imperator (initially a military honorific title) was only the princeps senatus, submitted to the same law as others.

It remained so even in Byzantium, despite the orientalization of the emperor’s status. The political hierarchy of Byzantium, Anthony Kaldellis wrote, was “an aristocracy of service, not blood, despite the occasional rhetoric.” The ruling élite “was marked by high turnover and had no hereditary right to office or titles, and no legal authority over persons and territories except that which came from office.” “families became powerful only when they succeeded in court politics and managed to retain imperial favor.”[1] Kaldellis also provides examples of “episodes when the people of Constantinople took the initiative to defend and enforce their views when it came to religious, political, fiscal, and dynastic matters, or when they disliked an emperor and wanted to get rid of him.”[2] I would argue that a people’s capacity to get rid of an incompetent or corrupted leader is much more precious than the illusion of having elected him in the first place. I found Byzantine society very interesting to study, because in many ways, Russia inherited the Byzantine political tradition, and it is not working so bad (see my article “Byzantine revisionism unlocks world history”).

Roman economy relied on slavery. Slaves were not citizens. They were excluded from the laws of the Republic—although there were special laws for them. But slaves, whether captured on the battlefield or bought from Jewish merchants, could be emancipated, and frequently were. They became freedmen. Freedmen were excluded from any role in leadership, but the offspring of freedmen were freemen.[3] Any freeman, with enough virtù and good fortune, could rise in the leadership. The shortest way was through military merit—not the worst test for the virtues of leadership. There were other forms of public service that could lift a man up the social ladder.

“Public life in the Roman Empire,” Peter Heather wrote, “is best understood as working like that of a one-party state, in which loyalty to the system was drilled into you from birth and reinforced with regular opportunities to demonstrate it.”[4] That’s a fruitful comparison. A Republic is supposed to be a system where all citizens, regardless of their social rank, live under the same law and have the same opportunities—given a few generations, if you start as a peasant. A Republic, in other words, is not necessarily a democracy, but it is, in theory, a meritocracy. And arguably the one-party-system, as in China with the CPC (Communist Party of China), is not a bad system for the selection of men of talent, merit, and virtù. It produced Xi Jinping. I wish my democratically elected president would be this kind of leader.

The illusion of representative democracy

The overthrow of the ruling class by the “working class” has been the aim of the revolutionary movements of the last two centuries. From the point of view of a “Machiavellian” political scientist like Mosca, overthrowing a ruling class is possible, but having “the people” rule is impossible. Therefore, the modern democratic ideology—the idea that each man has an equal say in political affairs—is a lie. It is a universal law, according to Mosca (p. 336), that “in all forms of government the real and actual power resides in a ruling minority.” Democratic regimes must conceal this truth and pretend that there is no such thing as a ruling élite. According to Burnham, vilifying Machiavelli is part of this concealment. Democracy is founded on the idea of “popular sovereignty”, a fantasy of Rousseau (to his defense, Rousseau warned that Democracy could only work at the level of the city, a unit of civilized people sharing a common culture and a common interest).

One of the authors that Burnham includes among the “Machiavellians” is the German-Italian sociologist Robert Michels (1876-1936). In his book on Political Parties, Michels shows that all democratic organizations tend to become oligarchic. His criticism of democracy is particularly interesting. Here is Burnham’s paraphrase (p. 145):

The truth is that sovereignty, which is what—according to democratic principle—ought to be possessed by the mass, cannot be delegated. In making a decision, no one can represent the sovereign, because to be sovereign means to make one’s own decisions. The one thing that the sovereign cannot possibly delegate is its own sovereignty; that would be self-contradictory, and would simply mean that sovereignty has shifted hands. At most, the sovereign could employ someone to carry out decisions which the sovereign itself had already made. But this is not what is involved in the fact of leadership: as we have already seen, there must be leaders because there must be a way of deciding questions which the membership of the group is not in a position to decide. Thus the fact of leadership, obscured by the theory of representation, negates the principle of democracy. … A mass which delegates its sovereignty, that is to say transfers its sovereignty to the hands of a few individuals, abdicates its sovereign functions.

Democratic countries are still ruled by élite groups. In the ideal case, it is a “government for the people,” but never a “government by the people”. The élite make the big decisions. In the U.S., they run foreign policy—in other words, the Empire—through elitist organizations such as the Council on Foreign Relations. One longtime CFR member, Zbigniew Brzezinski, explained in his book The Grand Chessboard (1997) that democracy and imperialism are hardly compatible, because the people don’t normally vote for war, unless lied to. Because imperial strategies are best kept out of the public debate, the United States developed, during the Cold War, into a two-level state, as Michael Glennon explains in National Security and Double Government (Oxford UP, 2016). In the backstage of the “Madisonian institutions” — the President, Congress, and the courts — there is another government, popularly known as the deep state, but more appropriately named the National Security State, which operates outside constitutional and electoral control. Glennon names it the “Trumanite network” because it was President Truman who created the first structure of this “state within the state.” The Bank (global finance) must be added to the equation as part of the non-democratic deep powers.

The one-percent ruling class also organizes itself through more secretive groups like the Bilderberg Group, who meet under the Chatham House Rule. This does not look very democratic, since democracy requires transparency from the decision-makers. It produces an understandable suspicion by the population that “they” conspire against “us”. Conspiracy theories easily get carried away, as with Alex Jones’ wild claims of Satanic child sacrifice in the Bohemian Grove summer camps (read my article about it). The Bohemian Club is actually a good example of a tool for “ruling-class cohesiveness”, as William Domhoff calls it in Bohemian Grove and Other Retreats: A Study in Ruling-Class Cohesiveness (HarperCollins, 1975). It is quite natural that people who are excluded from such élite scout camps (not even women are allowed in the Club) fantasize about it.

At the root of all those wild conspiracy theories, there is a profound disillusion about our democratic system. This disillusion is of course legitimate. But most people, in their disillusion, are still captive of the illusion that true democracy is possible, if only we would put the current ruling elite in jail. This illusion must be dispelled: there is no such thing as true democracy, and there will never be. Democracy is a lie. Because it is a lie, it attracts liars in government office, and it ultimately becomes the rule of liars. Lying becomes the quality required for becoming part of the ruling class. No one can be elected by telling less lies than his rivals, when voters are already brainwashed by lies. Liars can be bought and sold. They will lie even better when blackmailed. And men who have no regard for the truth will have also only contempt for the people they are supposed to lead.

Of Jews and Huns (but not every Hun)

Ultimately, democracy becomes an easy target for the “Great Master of Lies” (Schopenhauer as quoted by his most famous Austrian disciple). This foreign conquering and highly organized people forms now the true ruling class, the handlers of our elected officials, dictating them their talking-points, holding the president’s hand to sign their documents, trying the convince the masses that democracy is primarily about fighting anti-Semitism. A foreign, hostile, mean, religiously endogamous, supremacist, sociopathic, vengeful, and paranoid ruling class, has taken control of the U.S. MAGA and PNAC are deceptive slogans waved by people whose real and only objective is to make Israel great and to make the twenty-first century an Israeli Century (after the previous “Jewish Century”).

Our Jewish ruling class abide by a book that reflects their origin as a semi-nomadic people living primarily from looting, and obsessed by the accumulation of transportable wealth, gold in particular. Their empire over Westerners actually resembles what historians call the Hunnic Empire of the fifth century in central Europe, built upon the subjection of Gothic agricultural bands in the lands north of the Lower and the Middle Danube, through devastating warfare, pillage, and extortion of tributes. Roman historian Priscus wrote about the Huns: “These men have no concern for agriculture, but, like wolves, attack and steal the Goths’ food supplies, with the result that the latter remain in the position of slaves and themselves suffer food shortages.”[5]

Funerary archaeology offers an illuminating perspective on the relationship between Huns and their Gothic subjects, as Peter Heather relates:

a striking feature of the excavated material is the contrast between the large number of unfurnished burials and a smaller number of rich ones. These rich burials are not just quite rich: they are staggeringly so. They contain a huge array of gold fittings and ornamentation … The presence of so much gold in Germanic central and eastern Europe is highly significant. Up to the birth of Christ, … gold was not being used to distinguish even elite burials at this point—the best they could manage was a little silver. The Hunnic Empire changed this, and virtually overnight. The gold-rich burials of the ‘Danubian style’ mark a sudden explosion of gold grave goods into this part of Europe. There is no doubt where the gold came from: what we’re looking at in the grave goods of fifth-century Hungary is the physical evidence of the transfer of wealth northwards from the Roman world that we read about in Priscus and the other written sources. The Huns … were after gold and other moveable wealth from the Empire—whether in the form of mercenary payments, booty or, especially, annual tributes. Clearly, large amounts of gold were recycled into the jewelry and appliqués found in their graves. The fact that many of these were the rich burials of Germans indicates that the Huns did not just hang on to the gold themselves, but distributed quantities of it to the leaders of their Germanic subjects as well. These leaders, consequently, became very rich indeed.

The reasoning behind this strategy was that, if Germanic leaders could be given a stake on the successes of the Hunnic Empire, then dissent would be minimized and things would run relatively smoothly. Gifts of gold to the subject princes would help lubricate the politics of Empire and fend off thoughts of revolt. Since there are quite a few of burials containing gold items, these princes must have passed on some of the gold to favoured supporters. The gold thus reflects the politics of Attila’s court. … Equally important, the role of such gold distributions in countering the endemic internal instability, combined with what we know of the sources of that gold, underlines the role of predatory warfare in keeping afloat the leaky bark that was the Hunnic ship of state.[6]

One of Attila’s systematic demand on the Romans, besides extorting gold in exchange for not rampaging their land, was the return of any fugitive who had taken refuge in the Empire. This demand was often granted, and the returned fugitives were impaled as an example to others. “Impaling seems to have been the main method of dealing with most problems in the Hunnic world,” Heather writes.[7]

There are interesting comparisons to be made here, with the ancient Hebrews. Replace “Huns” by “Jews” and “Goths” by “Gentiles” and you have a pretty good historical metaphor of what is happening in America today. Both the Hunnic Empire and the Jewish Empire function by making the leaders of the subject people rich, and impaling the fugitives of the system—AIPAC money and ADL cancelling. In “The Cursed People”, I have hypothesized that the Mosaic religion is rooted in the preexisting cult of the nomadic Kenites, who cultivated a reputation of being extremely vengeful, practicing “sevenfold” or “seventy-sevenfold vengeance” (Genesis 4:15, 24).

No one knows what happened to the Huns after they retreated back to their Eurasian steppe following Attila’s death. The Huns did not write, and we don’t even know what language they spoke (they used Gothic as lingua franca).

The Jews, on the other hand, are the people of the Book. For that reason, they became fossilized in the mindset that shaped their book. The ʿApiru were wandering raiders and parasites, and so the “Hebrews” remained, because that’s what their volcano god told them to be, promising them a country “with great and prosperous cities you have not built, with houses full of good things you have not provided, with wells you have not dug, with vineyards and olive trees you have not planted” (Deuteronomy 6:10-11). The prophets of old continue to this day to encourage the parasitic nature of Israel: “You will suck the milk of nations, you will suck the wealth of kings” (Isaiah 60:16); “Strangers will come forward to feed your flocks, foreigners will be your ploughmen and vinedressers; but you will be called ‘priests of Yahweh’ and be addressed as ‘ministers of our God’. You will feed on the wealth of nations, you will supplant them in their glory” (Isaiah 61:5-6); “the wealth of all the surrounding nations will be heaped together: gold, silver, clothing, in vast quantity” (Zechariah 14:14). The god of Israel is obsessed with gold and silver: “I shall shake all the nations, and the treasures of all the nations will flow in, and I shall fill this Temple with glory, says Yahweh Sabaoth. Mine is the silver, mine the gold! Yahweh Sabaoth declares” (Haggai 2:7-8). The Jerusalem Temple was to be filled with gold, not God: “All the silver and all the gold, everything made of bronze or iron, will be consecrated to Yahweh and put in his treasury” (Joshua 6:19).

Let’s be fair, the Israelites were vastly superior to the Huns: more than a millennium before Attila, Moses (or Ezra reinventing Moses in Babylon) understood that usury was the ultimate form of parasitizing, and that entire nations could be enslaved through debt: “If Yahweh your God blesses you as he has promised, you will be creditors to many nations but debtors to none; you will rule over many nations, and be ruled by none” (Deuteronomy 15:6).

[1] Anthony Kaldellis, Streams of Blood, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium 955 A.D. to the First Crusade, Oxford UP, 2017, p. 5.

[2] Ibid., p. 124.

[3] Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History, Macmillan, 2005, p. 94.

[4] Ibid., p. 132.

[5] Ibid., p. 361.

[6] Ibid., pp. 364-5.

[7] Ibid., p. 321.